All our dreams can come true if we have the courage to pursue them. —Walt Disney

Many of us are familiar with the story: a young Walt Disney was fired from his newspaper job because he “lacked imagination”! Learning that one of the world’s most creative and successful entrepreneurs struggled through his own share of rejection, is incredibly inspiring for the rest of us wannabes. Unfortunately, Uncle Walt never worked for a newspaper. He did work for an ad agency, however; only he was never fired from the company.

It’s impossible to find a reliable source for this fanciful anecdote. Like most urban legends, someone somewhere got the facts wrong, and we’ve been repeating the “story” ever since. But it’s all good. Disney did have his share of misfortunes, and he did face many naysayers in the course of achieving his dreams — including two in his own family!

It’s impossible to find a reliable source for this fanciful anecdote. Like most urban legends, someone somewhere got the facts wrong, and we’ve been repeating the “story” ever since. But it’s all good. Disney did have his share of misfortunes, and he did face many naysayers in the course of achieving his dreams — including two in his own family!

One obstacle Walt Disney dealt with repeatedly was financing. In the early 1950s, when Disney announced his plans to construct a 160-acre theme park in California, there were no investors lining up to help foot the bill — which ultimately grew to $17 million. Disney was turned down by so many banks that he finally devised an alternate means of funding the project: he created a weekly anthology show called Disneyland, which he gave to the fledgling American Broadcasting Network. ABC was ranked third behind CBS and NBC, so the “alphabet network” benefited greatly from airing the popular show. In return, ABC joined with Western Publishing (which had gotten the rights to publish comics and activity books based on Disney characters) in bankrolling Disney’s dream world.

Disneyland opened in 1955 and immediately became one of the chief destinations of vacationers from across the globe. There’s an ancient proverb that “a fool and his money are soon parted,” but that certainly wasn’t the case with Walt Disney. He may have had the most grandiose dreams, but he was no fool — contrary to what his critics thought.

Disney hadn’t always been the best business manager, though. Based on the financial success of his earliest cartoons, he and his brother Roy had purchased their own animation studio, Laugh-O-Gram, in 1922. Then Disney recruited the best animators he could find, paying each of them a salary far more generous than Disney could balance against his studio’s profits. Within months, Laugh-O-Gram went bankrupt.

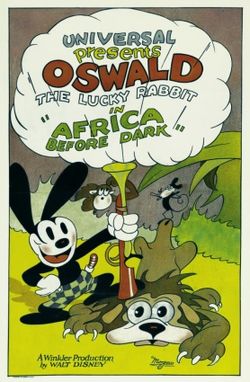

Further defeats lay ahead of Disney. His first breakout cartoon character was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a comical and “exceptionally clever” creation that was not only a hit at the movies, but which also made beaucoup bucks in merchandising. But Uncle Walt saw very little of the profits; he’d signed a contract with Universal Pictures which gave the studio complete ownership. Eventually Universal hired away most of Disney’s animators and then took over the production end of the Oswald cartoons. Universal had gotten a “Lucky Rabbit.” Walt had gotten the boot!

Further defeats lay ahead of Disney. His first breakout cartoon character was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a comical and “exceptionally clever” creation that was not only a hit at the movies, but which also made beaucoup bucks in merchandising. But Uncle Walt saw very little of the profits; he’d signed a contract with Universal Pictures which gave the studio complete ownership. Eventually Universal hired away most of Disney’s animators and then took over the production end of the Oswald cartoons. Universal had gotten a “Lucky Rabbit.” Walt had gotten the boot!

Such failed business ventures don’t exactly bolster confidence in one’s ability to succeed. Which is why the creator’s next project was universally greeted with dismay. Uncle Walt wanted to do something that had never been attempted before; he wanted to produce a feature-length animated movie — based on the children’s fairy tale, Snow White. He also wanted realistically rendered human characters and elaborate special effects. To create his unorthodox masterpiece, Disney would need to hire an art professor to train his animators in a more realistic style of design; and the studio would need to experiment with advanced processes and, hence, purchase all new equipment, such as a multiplane camera.

When the film industry learned of the project, they jokingly dubbed it “Disney’s Folly,” confident that such a movie couldn’t be made and that attempting such an audacious feat would ruin Disney Studios. And it almost did. The production, which commenced in early 1934, took the better part of three years, and before the movie was finished the studio did indeed run out of money. In order to finance the remaining work, Uncle Walt screened a rough cut of the film to a group of investors who applauded it.

Meanwhile, Disney’s brother Roy begged the creator not to gamble with the studio’s future. And even Disney’s wife pleaded with him to drop the project. But Disney refused to give up on his dream. He also refused to let his past mistakes define him, or to listen to well-intentioned advice from people who couldn’t catch the vision. Then again, perhaps he was just stubborn.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarves was the most successful movie of 1938. During its initial run, the film earned $8,000,000 — which today is roughly equivalent to $135 million. Disney was often, precariously, parted from his money, but he was no fool. Just a dreamer.

Don’t allow yourself to be defined by past failures. Dream big. Follow your instincts and the leading of the Lord. “You will hear a voice behind you saying, “This is the way. Follow it, whether it turns to the right or to the left.” (Isaiah 30:21 GW)