He was a popular Victorian writer of short stories and novels, whose work had met with both critical and popular success. But at the age of 30 he found it increasingly difficult to duplicate the same level of financial success he’d enjoyed with his earlier books. In fact, his literary career was in steep decline.

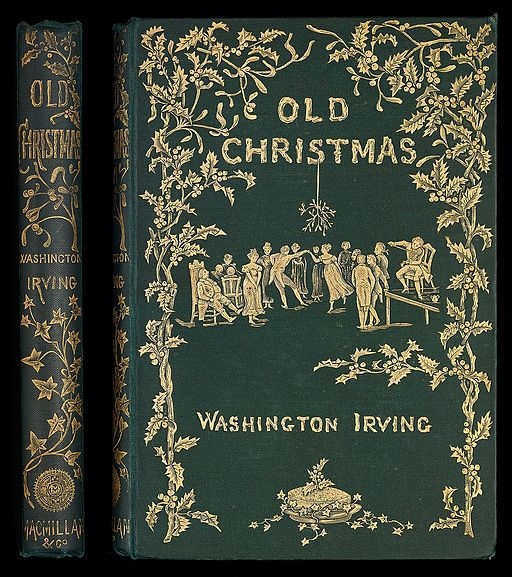

This British writer had mounting debts to pay and an expectant wife to support, so he reaccessed his work and the way in which he presented it. He searched for fresh ideas and found one he felt could get his byline back on the covers of the popular literary magazines. And he took inspiration from the work of a fellow writer, Washington Irving, the American novelist who’d produced the creepy classic The Ghost of Sleepy Hollow.

This British writer had mounting debts to pay and an expectant wife to support, so he reaccessed his work and the way in which he presented it. He searched for fresh ideas and found one he felt could get his byline back on the covers of the popular literary magazines. And he took inspiration from the work of a fellow writer, Washington Irving, the American novelist who’d produced the creepy classic The Ghost of Sleepy Hollow.

Twenty years earlier, Irving had noticed a renewed interest in Christmas traditions, in both the U.S. and Great Britain, and had penned several successful holiday-themed tales. Both Irving and his British contemporary approached their work in similar fashion–and both men enjoyed a good ghost  story.

story.

Influenced by the tales of Irving, and remembering the long-held wintertime tradition of recounting spooky legends of ghosts and goblins by the fireside, the struggling British writer realized he could meld the two genres for his next project!

He’d unearthed the basic skeleton for a cracking good read, but as yet his story lacked a heart. He searched for that heart during long hours of contemplation, when he “walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed.” And he found it at last after a visit to Manchester’s factory district, where he observed the pitiful state of the poor and their wretched working conditions, a sight that reminded him of his own childhood days spent working in a glue factory. He suddenly realized his Christmas story could be used to strike “a sledge hammer blow” for society’s neglected and needy classes.

He hoped his tale would create greater public awareness of their plight, and encourage his readers to reach out to their less fortunate brothers and sisters — especially at Christmastime, “a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers … and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.” He completed his cautionary tale in six weeks, and planned to have it published early in December, 1843.

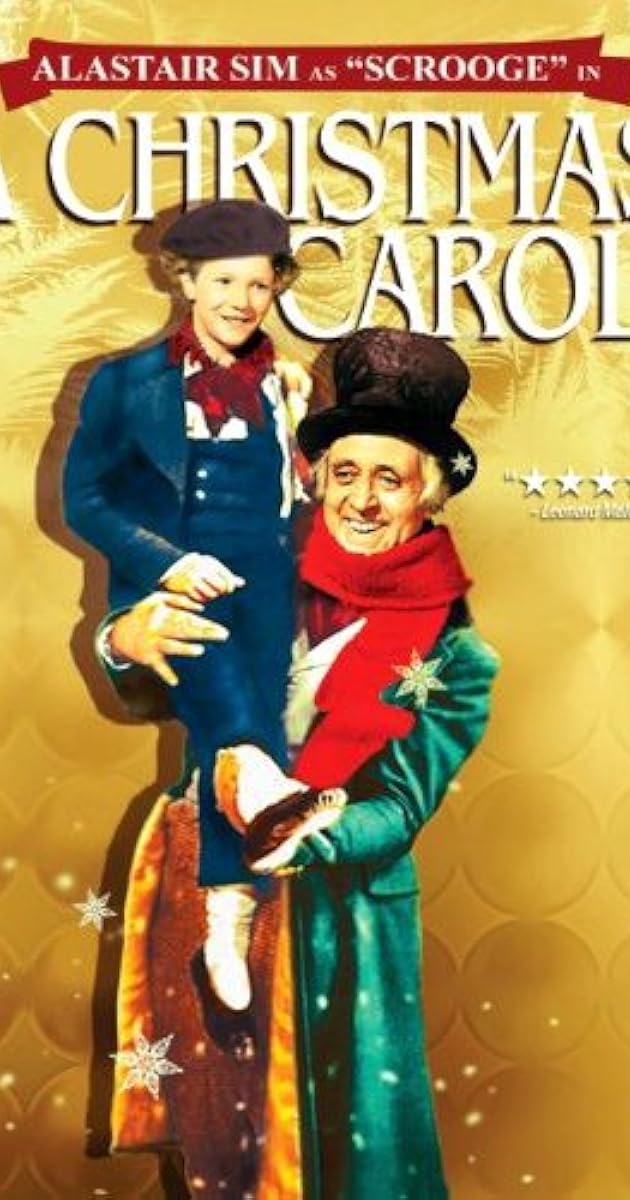

Not satisfied with the pathetic sum his last publisher paid him, the writer had decided to pay for publication of the story from his own pocket, and hence enjoy a greater share of the book’s profits. He felt the book would be popular at Christmas and hurried to have it ready in time for holiday shoppers (and readers); but two separate production errors delayed the book’s publication. With less than five shopping days left, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol finally arrived in bookstalls late on December 19th!

To cover the cost of printing the initial 6,000 copies — and realize enough profit to cover his family’s living expenses, Dickens hoped to net £1000 from sales (£20,000 by today’s standards, or roughly $30,000). But although the book had completely sold out by Christmas Eve, the writer made less than one-fourth that amount! An additional printing was quickly prepared and it too sold out shortly after the New Year; and by May of 1844, a seventh printing had sold out!

To cover the cost of printing the initial 6,000 copies — and realize enough profit to cover his family’s living expenses, Dickens hoped to net £1000 from sales (£20,000 by today’s standards, or roughly $30,000). But although the book had completely sold out by Christmas Eve, the writer made less than one-fourth that amount! An additional printing was quickly prepared and it too sold out shortly after the New Year; and by May of 1844, a seventh printing had sold out!

A Christmas Carol was both a critical and popular success, but the book’s profits continued to disappoint Dickens. And as if to rub salt into his financial wounds, a rival publisher pirated the book and began printing a competing edition! Dickens immediately filed a lawsuit, but the publisher just as quickly filed for bankruptcy, and poor Dickens was left with all the legal fees!

But it’s Christmastime, and we can’t have Dickens’ literary adventures end on a sour note: a few years later, the writer realized audiences would actually pay to watch him read his book on stage; and after 127 packed-house “performances,” A Christmas Carol finally provided the sound financial returns Dickens’ had hoped for!

You know the rest: since its publication, A Christmas Carol has never been out of print; it’s a perennial classic that’s sold millions of copies and been adapted for stage, screen, radio and television. And despite a couple of bumps in the road to its publication, and a little sweating over its profitability, Dickens proved that a dollop of creativity, some savvy marketing, and a lot of faith can go a long way!

You know the rest: since its publication, A Christmas Carol has never been out of print; it’s a perennial classic that’s sold millions of copies and been adapted for stage, screen, radio and television. And despite a couple of bumps in the road to its publication, and a little sweating over its profitability, Dickens proved that a dollop of creativity, some savvy marketing, and a lot of faith can go a long way!

Dear dreamers and fellow creators, “May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One!”

“Let us not lose heart in doing good, for in due time we will reap if we do not grow weary.” (Galatians 6:9 NASB)